Since its formation as an independent nation, The United States of America prides itself as the embodiment of the ideals of "freedom, liberty, and justice for all." It is known as the "land of the free" and a virtual melting pot, where different races and nationalities can live amongst each other peacefully. America is a nation formed from a vast majority of immigrants, settled in pursuit of a better life and greater opportunity. Such beliefs and opportunities lured hundreds of thousands of persons of Japanese ancestry to settle within United States territory. During 1942-1946 people of Japanese decent, known as Japanese Americans were denied their freedoms and rights. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the nation of Japan on December 7, 1941, the American government panicked with threatening thoughts of dangerous enemies existing within the country. All individuals of Japanese ancestry were considered potential enemies of the United States, as result of government Order 9066, over 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were forced into relocation camps (Harding, National Museum of American History). These camps, known as Japanese internment camps, were established in an effort to remove those seen as potential enemies from society. Approximately 70 of such camps are acknowledged as having existed within the United States. This paper will discusses the political actions of the United States of America leading up to the formation of the relocation camps and the relocation order, known as Executive Order 9066; defines the different classifications of Japanese Americans and examine the question of their "loyalty" to the United States; and examines the quality of life within the relocation camps.

During the period from 1941 to 1946, the United States government faced a great deal of political pressure to create a sense of security for Americans. The U.S. was involved in World War II, the Draft was enacted, and after Pearl Harbor Americans began to see themselves as vulnerable after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Private citizens in small towns and large cities feared the horror of the warfront, and the possibility, however remote, of the United States becoming such a "war zone." Even greater than the fear of the gore of the warfront, was the threat of an external government using spies and infiltrating the U.S. government from within the normal social structure. Suspicions ran high. People questioned the loyalty of immigrants, foreigners and neighbors alike. Immigrants, especially of German, Italian and most of all, anyone of Japanese ancestry, became prime targets. An example of such fear was evident in the following quote from a newspaper article: "People began asking what 18,000 Japanese aliens in this State [California] ...might do to sabotage defense plants or to aid invaders if they were permitted to live and travel without restriction" (New York Times, February 14, 1942). It was this fear which served as the driving target leading to the government's formation of relocation camps. The camps were a way to monitor activities of persons of Japanese ancestry. Their separation from society made contact with the outside world, and especially the enemy country of Japan, nearly impossible. The containment of these people was seen as an essential safety matter to maintain American perceptions of safety and superiority.

Discrimination against persons of Japanese descent occurred long before World War II. The imposing war in 1941 only aggravated a preexisting desire of America to take action in maintaining power over an increasing minority population. America's lack of knowledge and understanding of the Japanese American people and their culture lead to unnecessary fear. With the excuse of Nation Security, the U.S. government quickly enacted National and State Laws, Acts of Congress, and other acts in attempts to control the persons of Japanese ancestry, deeming them "dangerous enemies" (Daniels. 1986).

Asian immigrants were targeted for discrimination by the United States government as far back as 1913, when the California Alien Land Law prohibited "aliens ineligible to citizenship" (i.e. all Asian immigrants) from owning land or property, but permitted leases of up to three years (Harding). Prior to this law, acres of farmland in California belonged to Japanese Americans. By 1925, similar laws were passed in Washington, Arizona, Oregon, Idaho, Nebraska, Kansas, Louisiana, Montana, New Mexico, Minnesota, and Missouri. During World War II, Utah, Wyoming, and Arkansas also enacted the same such laws (Harding).

In 1922, in Ozawa v. U.S., the Supreme Court reaffirmed that Asian immigrants were not eligible for naturalization. In June of 1935, Congress passed an act making aliens otherwise ineligible for citizenship eligible only if (a) they had served in the U.S. armed forces between April 6, 1917 and November 11, 1918, and been honorably discharged, and (b) they were permanent residents of the United States. A small number of Japanese-Americans, classified as Issei, obtained citizenship under this act before the deadline on January 1, 1937 (Daniels).

On November 26, 1941 Henry Field was order by Roosevelt to produce a list, in the shortest time possible, of the full names and addresses of each American-born and foreign-born Japanese listed by locality within each state (Daniels).

On December 7, 1941, the nation of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle gave orders to the FBI to arrest a predetermined number of "dangerous enemy aliens," from Field's lists, including 737 Japanese Americans (Daniels). America officially entered into World War II on December 8, 1941. On December 11, 1941, an additional 1,370 Japanese Americans were arrested by the FBI and classified as "dangerous enemy aliens" (Daniels).

The Agriculture Committee of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, on December 22, 1941, recommended that all Japanese nationals be put under "absolute Federal control" (Daniels, 1986). On this date, many Japanese Americans in the military, now classified as enemy aliens, were demoted to menial labor or discharged (Daniels).

Shortly after, on December 29, 1941, all "enemy aliens," as Japanese Americans were classified, in the states of California, Oregon, Washington, Montana, Idaho, Utah, and Nevada were ordered to surrender contraband. (Daniels, 1986). One day later, on December 30, 1941, Los Angeles Congressman Leland Ford, sent a telegram in which he stated "I do not believe that we could be too strict in our consideration of the Japanese in the face of the treacherous way in which they do things," and went on to request all Japanese Americans be removed from the West Coast (Daniels, 1986).

On January 29, 1942 Attorney General Biddle began the establishment of prohibited zones forbidden to all enemy aliens, resulting in the orders for Japanese Americans to leave the San Francisco waterfront areas (Daniels). On February 4, 1942 Attorney General Biddle established 12 "restricted areas" in which Japanese Americans were restricted by a 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. curfew, allowed only to travel to and from work, and no more than a distance of five miles from their home. The restricted zones, to which the regulations applied, extended inland from the Pacific Coast as much as 150 miles (New York Times, February 5, 1942).

After many attempts by congressional delegation to restrict and/or remove all persons of Japanese ancestry from what were deemed "strategic areas" of California, Oregon, and Washington, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sealed the fate of all persons of Japanese descent on February 19, 1942, signing Executive Order 9066. Executive Order 9066 authorized the secretary of war to define military areas "from which any or all persons may be excluded as deemed necessary or desirable" (Daniel, 1986). Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, appointed Lieutenant General John DeWitt to carry out Executive Order 9066.

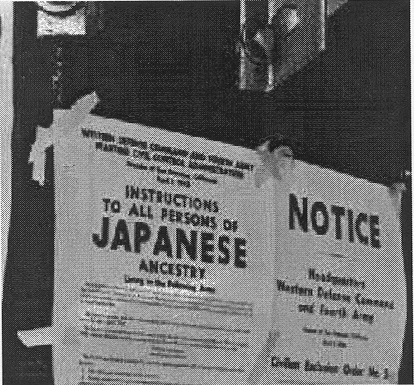

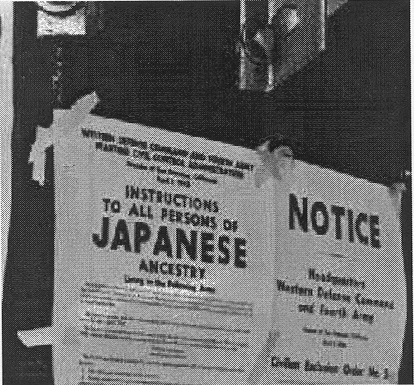

After Executive order 9066, a campaign of posters was used to inform the Japanese American public, along with other communication measures, revealing relocation details. Below is picture of an actual poster:

After Executive Order 9066, posters order all Americans with Japanese ancestry out of their homes.

Photo by Dorothea Lange

The Library of Congress, Dorothea Lange, (c) 1995.

"Evacuees" were limited to bringing only "that which can be carried by the individual or family group." Thus, Japanese Americans were forced to leave behind furniture, homes and beloved pets. Although promised storage for items they were not able to sell for fair prices, very few Japanese Americans trusted the U.S. government's word. Instead many sold items for next to nothing, and other merchants often exploited the panicked Japanese American population. Yet, hoping to avoid harsher infractions or deportation, Japanese Americans, and the Japanese American Citizen's Leagues often published pledges to aid and cooperate in the evacuation and relocation proceedings. One such article states, "Be it resolved the that the Japanese American Citizens League of Seattle go on record as endorsing cheerful and willing cooperation by the community with the government agencies in carrying out of the evacuation proceedings" (New York Times, Monday April 20, 1942).

Businesses were often affected by evacuations; U.S. government seized fishing boats and stores. Only those declared too ill by medical institutions were allowed to remain in treatment facilities outside of the relocation hospital facilities. In all, over 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were affected by Executive Order 9066, and of those relocated, nearly two thirds were United States citizens (Harding & Angle, 1988- National Museum of American History Archives).

Fishing boats left behind by incarcerated Japanese Americans were later sold for a fraction of their value. Photo by Dorothea Lange from Bernard K. Johnpoll Ed. by Roger Daniels et al. Japanese Americans, from Relocation to Redress; University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah, (c) 1986, p. 164

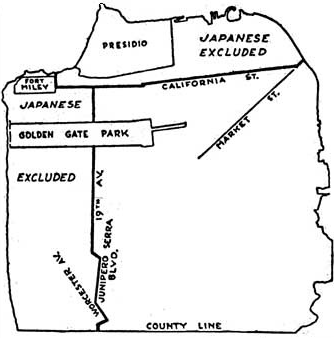

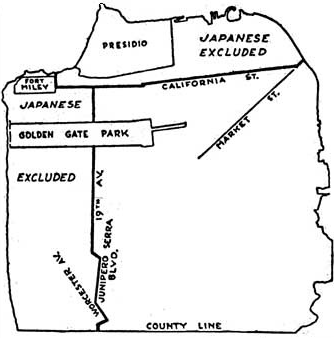

The following excerpt from the San Francisco News, April 2, 1942 edition, exemplifies the seriousness of the relocation orders: "After more than a month of offering advice and suggestions to Japanese in the coastal military area, the Army today was issuing blunt orders to those who failed to leave voluntarily before the deadline last Sunday midnight. Lieut. Gen. John L. DeWitt designated as the first area to be evacuated, 'all the portion of the City and County of San Francisco lying generally west of the north-south line established by Junipero Serra-av, Worchester-av and 19th ave and lying generally north of the east-west line established by California-st to the intersection of Market-st and then on Market-st to the Bay.' A Civil Control Station was opened at 1701 Van Ness-av, and General DeWitt directed that a responsible member of each family, and each individual living alone, report there between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. today or tomorrow." The below map represents the physical area described above.

Original caption was: "Here's the San Francisco area covered by the first evacuation order issued by Lieut. Gen. John L. Dewitt. All Japanese must be out of the area beyond the black line by Tuesday." San Francisco News Graphic, 1942

These stern orders with military enforcement made Japanese Americans, citizens as well as resident aliens, question their security and well being. In a letter to Mrs. Roosevelt, they requested the acknowledgement that something would be done (New York Times, April 7, 1942). Mrs. Roosevelt responded, "I know the many difficulties confronting the American-born Japanese and also the loyal Japanese Nationals. I am confident that the government will do everything possible to make the evacuation as descent and as comfortable as possible, and it will provide protection" (New York Times, April 7, 1942). Judging from the poor condition these individuals endured within the relocation camps, there remains question if Mrs. Roosevelt's remark was ever acted upon.

Fear of Japanese Americans was further exemplified in daily societal activities. One such example is the renaming of Japan Street to Collin Kelly Street in San Francisco. On February 9, 1942, "The name of Japan Street, in the waterfront district...was changed by the Board of Supervisors...to Collin Kelly Jr. Street, honoring the Army flier who sank a Japanese battleship." (New York Times, February 10, 1942). This renaming demonstrates America's need to exemplify superority over the country of Japan, as well as Japanese-Americans.

Clearly the United States Government felt a compelling need to enforce Executive Order 9066 and the subsequent relocation and internment of Japanese Americans. However, there is evidence that such actions were unnecessary and the result of public pacification rather than necessary national safety. During October and November of 1941, Roosevelt appointed Special Representative of the State Department, Curtis B. Munson, to conduct an intelligence investigation on the loyalty of Japanese Americans. According to his findings, "the Issei, or first generations, is considerably weakened in their loyalty to Japan by the fact that they have chosen to make this their home and have brought up their children here. They are quite fearful of being put in a concentration camp.... have to break with their religion, their god, ...ancestors and their after-life in older to be loyal to the United States.... Yet they do break, and send their boys off to the Army with pride and tears....They are good neighbors." (Daniels) Issei were defined as having an entirely Japanese cultural background and still legally having Japanese citizenship. Most Issei were within the age range of 55 to 65 and were eager to acquire U.S. citizenship. Children of Issei born within the U.S., or its territory, became citizens by birth. Munson's findings also declared them to be of little threat to the U.S., and he reported of their knowledge of America's possible plans to remove them from society and their fear of being sent to concentration camps.

Munson's report was important in defining who were considered "enemy aliens" by the U.S. Government, as Munson names four additional classes of Japanese Americans. The Nisei were "second generation Japanese who have received their whole education in the United States, in spite of discrimination against them...(they were) estimated from 90-98 percent loyal to the United States ...The Nisei are pathetically eager to show this loyalty ... Though American citizens they are not accepted by Americans, largely because they look differently" (Daniels). An important division of the Nisei is the Kibei, or those Americans of Japanese decent that were educated in Japan. The Kibei were again divided into those that were educated in Japan as children and those that receive education in Japan later in life (age 17 and older). Treated as foreigners in Japan, the Kibei were said to "come back with added loyalty to the United States" (Daniels).

The Sensei was considered those in the third generation of Japanese descent. During the period of encampment, these were the very young children and babies. Munson asked the government to "disregard for the purpose of our survey" (Daniels).

The final classification of Japanese was the Hawaiian Japanese. Munson described these individuals " (they) do not suffer from the same inferiority complex or feel of mistrust of the whites...on the mainland.... Hawaii is more of a melting pot...absolutely no bad feelings between the Japanese and the Chinese...why should they be any worse towards us?" (Daniels) In all, he declared all of the above listed classifications of Japanese Americans to be highly loyal, hard working, and able to get along with others. Munson goes on in his report to claim, "The story was all the same. There is no Japanese 'problem'...there will be no armed uprising of Japanese" (Daniels). Munson's report was very important, as Munson was commissioned by the government in anticipation to discover disloyalty within the people of Japanese descent. Yet, his report concedes findings quite the opposite. In fact Munson reported loyalty to America ran very deep within the population of those persons of Japanese ancestry throughout the United Sates. Demonstrative of such loyalty, the organization known as Democratic Treatment for Japanese Residents in the Eastern States, "issued a statement ...pledging its membership to support the government of the United States and disavowing concern with Japanese policy...copies of which were sent to President Roosevelt and to Congress" (New York Times, August 14, 1941). Japanese Americans were trying very hard to declare themselves as loyal citizens and aliens, yet, their pledges of loyalty stood ignored by the U.S. government.

Declarations of loyalty to the United States, as well as the findings of Curtis Munson disproved persons of Japanese ancestry to be in any way a threat to the security of the United States. Yet, of their shared ancestry with the nation of Japan. U.S. officials ignored Munson's report and all supporting evidence proving the contrary. U.S. Government officials pacified national hysteria by enacting Executive Order 9066.

The persecution of people of Japanese ancestry transpired slowly, with the final blow being their forced movement to the relocation camps. Many similarities exist between the U.S. government and its treatment of the Japanese Americans, and the Nazi regime and its treatment of persons of Jewish descent. Both were persecuted on a basis of ancestry and forced to involuntarily relocate to guarded concentration camps. Those required to relocate to the camps were only allowed to take what they could physically carry. Common practice in both Nazi death camps, and America's Japanese Internment Camps was constant military guard, with orders to assonate anyone who tried to escape. Although, the U.S. Government did not murder hundreds of thousands of Japanese, starvation, improper shelter and clothing, and illness were rampant in the poorly constructed camps (Kashima). Milton Eisenhower, before the Senate Appropriation Committee, stated in regards to the camps: "[The Construction] is so very cheap that, frankly, if it stands up for the duration we are going to be lucky" (Weglyn, 1976).

After Executive Order 9066 was signed, "Assembly Centers," or temporary camps used from late March 1942 until mid-October, 1942, served to house the 110,000 plus Japanese American prisoners before they were moved to the permanent detention camps. Most of these "assembly centers" were either large fairgrounds or racetracks (Thomas, 1952).

The 70 Relocation Camps, often old, deserted military instillations, provided shelter in the form of small, poorly constructed tar and board shacks.

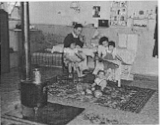

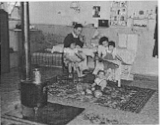

Sitting on homemade furniture in a 20' x 24' room in Tule Lake, Sept. 1942. A room of this size was often home to three couples. Edward Spencer et. al., Impounded People: Japanese-Americans in the Relocation Centers, University of Arizona Press, Tuscon, Arizona. (c) 1969.

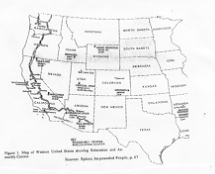

The exact number of Relocation Camps was not known, as the government claimed a complete listing was never compiled or released (Fallon/Jacobs, 1998). Most relocation camps were located in the western part of the United States.

Most camps were approximately one square mile, surrounded by barded wire, and guarded by military police in eight guard towers and the entrance station (World Book Online, " Manzanar National Historic Site"). According to the memories of Japanese Americans imprisoned within the internment camps, the following remarks regarding these facilities were made and recorded:

"After six months in a barracks at the Santa Anita Racetrack, we were sent to Heart Mountain, Wyoming. We arrived in the middle of a blinding snowstorm, five us children in our California clothes. When we got to our tar-paper barracks, we found sand coming in through the walls, around the windows, up through the floor." "The camp was surrounded by barbed wire." "Guards with machine guns were posted at watchtowers, with orders to shoot anyone who tried to escape."

(Thistlewaite, Manzanar National Historic Site- Web)

Within the camps, several families lived together in this one room dwelling, usually 16x20x24 feet. (Daniels, 1986). Camps contained barracks, one mess hall, and one recreation hall, ironing, laundry, and men's and women's lavatories. Households were assigned space according to the number of people in their household. Camps also contained schools, hospitals. Some facilities offered a library as well as places for religious services (Walz, 1997). While in these camps, children spent their days in camp schools. Often, young men either volunteered or were drafted for military service (Harding & Angle, 1988).

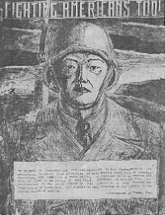

The military draft was in effect, and often, young men of Asian descent were called upon to serve in the military. Posters encouraging those of Japanese ancestry to serve, used the slogan "Fighting Americans Too!" (National Museum of American History Archives).

Many imprisoned within the camps felt it an outrage that they be forced to serve in the U.S. military. They felt the government had treated them poorly, denying them rights established by the Constitution and Bill of Rights. When one young man refused to register and conform to draft board orders, he was arrested and placed on trial. When questioned by authorities to reconsider, he replied, " Why should I [serve in the military] when the government has taken away our rights and locked us up like a bunch of criminals anyway? ...The government took my father away, and interned him someplace. My mother is alone at the Granada camp with my younger sister...if the government would take care of them here in America, I'd feel like going out to fight for my country, but this country is treating us worse than shit!" ( Tateishi, 1984)

Draft problems were not the only causes of unrest within the camps; there were several shootings of Japanese by military guards. In one shooting, the victims were two elderly men, Hirota Isomura and Toshio Kobata, both critically ill and too ill to walk with a group to a bus for a relocation center. While awaiting transportation, they were shot. The military claimed the men tried to run away. Other shootings all resolved similarly, as the U.S. government always seemed to claim the victims were trying to escape (Kashima, 1986).

U.S. involvement in World War II ended on August 14, 1945 with the surrender of Japan. Within a year, the last of the relocation camps was closed. The government enacted The Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, authorizing payment to Japanese Americans who suffered economic loss during the imprisonment: With necessary proof, 10 cents was returned for every $1.00 lost (Iritani, 1995). Yet, this futile attempt to compensate the Japanese American people seemed to serve more as an insult than an apology. In the end, the number of Japanese American persons convicted of war crimes against the United States was less than 10. Yet, over 110,000 were forced to suffer as result of mass hysteria and unfounded fears of national safety. One prisoner stated, "Our own government put a yoke of disloyalty around our shoulders. But, throughout our ordeal we cooperated with the government because we felt that in the long run, we could prove our citizenship" (Thistlewaite). In trying to prove this citizenship, many lost all their material possessions and financial assets. Executive Order 9066 came at a low cost to the U.S. government, but the cost to the Japanese American people was high. The losses of the Japanese American people during their internment in the relocation camps from 1942- 1946, cannot be totaled in dollar amounts, and the insult to their dignity cannot be forgotten.