Angela Hershberger graduated in May of 2002. This paper was written for her advanced lab, P429 Laboratory in Developmental Psychology, taught by Dr. Carolyn Schult.

Communicated By: Dr. Carolyn Schult, Psychology

Angela Hershberger graduated in May of 2002. This paper was written for her advanced lab, P429 Laboratory in Developmental Psychology, taught by Dr. Carolyn Schult.

Communicated By: Dr. Carolyn Schult, Psychology

Correlational research was conducted examining relationships between amounts of television viewing and school performance levels (e.g. GPA) reported by college level students for both variables during high school and college. Surveys were administered, which contained open-ended questions, aimed at both high school and college levels. Results indicated an inverse relationship between high school amounts of television viewing and high school GPAs, and no significance was found for college levels. A regression analysis and independent T-tests for three groupings of television programs viewed during college, also yielded insignificant results. Findings run counter to the majority of the current body of research, which finds amount of television has little effect on school performance levels. Research was also able to include previously excluded population in findings.

Since the 1950s, television has played a large role in everyday life. Almost every household within the United States contains at least one television set. What are the possible effects of television? Its impact has been indicated in many different areas such as creativity, violence, and even obesity (Hargborg, 1995; Myrtek & Scharff, 1996; Morgan & Gross, 1984). Scientific studies conducted thus far have concluded mixed results, and determining to what extent television affects individuals proves to be quite difficult. Although physiological measures are now being used, (e.g. heart-rate, blood pressure) the psychological measures are far more difficult to assess. As science attempts to determine the extent to which television affects individuals, the need for accurate and universal measures becomes essential. Since television is an instrument used for mass communication, its possible effects need to be investigated deeply.

Since television is such an integrated part of life, it demands further investigation into its potential "evils" and "benefits". Clarke and Kutz-Costes (1997) found indications that television-viewing time was negatively related to parental instruction and number of books found in the child's home. After examining the relationships among school readiness, television viewing, parental employment, and educational quality of home environment of 30 preschool students, they also found viewing time to be negatively related to the child's school readiness skills. Koolstra, Vander-Voort, and Vander-Kamp (1997) suggest these results could be due to less time spent reading, causing a reduction in reading skills. This theory remains one of the most prominent within the field to date. Many studies have been conducted in attempt to determine validity.

Yet others, such as MacBeth (1996), suggest television may be responsible for an increase in children's imagination and creativity. She claims that the role of television can actually boost participation in other activities, such as reading and drawing. It is believed that the increase in such activities might be responsible for the increase in persistence and school performance she found in her research. However, MacBeth was the only researcher to find such results.

Multiple studies, like one done by Myrtek and Scharff (1996), were able to find evidence of physiological effects of television viewing. They were able to show that different types of programs have effects on physiological measures (e.g. heart rate, blood pressure, etc.) and psychological aspects (e.g. I.Q. levels). They used exploratory research within their study design in order to collect direct data from a special ambulatory measuring device within the child's home. This device was able to measure the amount and type of shows watched, along with indications of emotional arousal. They also found that boys with high television consumption read fewer books, and showed a tendency for reduced school performance levels (Myrtek & Scharff, 1996).

Other studies were also able to find some correlation between television viewing and school achievement. Studies found that children with parents who set rules for television watching had higher IQs and received better grades in school. Also, the amount of television viewing was highly correlated with the viewing of all types of television programs, with the exception of sports. Larger amounts of television watching were associated with lower grades and lower IQs, and higher math grades were associated with sports, family, game, and cartoon show preferences (Ridley-Johnson, Cooper, and Chance, 1983).

Yet despite these findings, the majority of existing research (Childers & Ross, 1973; Gortmaker, Salter, Walker, & Dietz, 1990) all found relationships between television viewing and other factors to be of little or no significance. They stated that quantity was not a predictor of student achievement. Even a synthesis done by Williams, Haertel, Haertel, and Walberg (1982) of over 23 articles, dissertations, assessments, surveys, journal articles, reports, books, and unpublished papers found similar results. The overall effects were slightly positive for up to 10 hours of viewing time per week, but effects were negative beyond 10 until 35-40 hours per week in which there was no effect found.

Most of the research done to examine the relationship between television viewing and school performance has focused around grade school students, ranging from preschool to 8th grade levels. High school and college students should also be examined. They represent a large population missing from current research.

The focus of this research was to examine an overlooked population, much like that of the work of Hargborg (1995), who examined high school students in his research. He categorized students into one of three groupings: light, medium, and heavy television watchers. After examining background information, student-reported data, school attitudes, and intrinsic and extrinsic orientations in classroom, and self-perception, Hargborg (1995) found lack of significant differences in the groups in variables studied. Hargborg was, however, able to find a negative relationship between television viewing time and socioeconomic status. Unfortunately, Hargborg's study was the only one found in which the high school population was researched. With such small amounts of data collected on this population, it becomes nearly impossible to try to determine any sort of relationship.

Research has not yet been done comparing these two age groups and the effects of television watching during these time periods. Another important aspect of this research was to include reports of college level students television viewing habits, and school performance levels compared with levels reported during high school, and note changes in amounts of television viewed, and changes in school performance levels.

More adolescents and young adults need to be studied in order to attempt to either suggest or disprove hypotheses involving relationships between television and school performance among high school students. Since there has been no research conducted that examines the television viewing habits of college age students, it becomes near impossible to predict the direction of this research's end results.

Among college students it is predicted that there will be a slight inverse relationship between amount of time spent watching television in high school and high school performance levels. Furthermore, results will show little to no correlation between amount of television watched during college and college performance levels.

Participants

College students (M age= 24.72) enrolled in an introductory psychology course volunteered to participate. Students (n=50) signed up on a volunteer basis and received extra credit points to be used towards their class grade. Participants were treated in accordance with the "Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct" (American Psychological Association, 1992).

Materials

A survey was developed specifically for this research. It focused on the amount of television viewed by asking participants the average amount of television they watched per week and which shows they viewed regularly. Participants were also asked to check off types of programs viewed most regularly. These questions were asked for both high school and college. Basic demographic information was asked and both high school and college GPAs were collected. Questions were mainly open-ended.

Procedure

Research received IRB approval before any participants were run. All students received the same survey, which was administered by the researcher. Participants signed an informed consent form prior to participation, which outlined the focus of the research. An instruction sheet was provided which contained directions for filling out the survey. Participants were then asked to complete the survey.

Design

This research examined the correlational relationship between school performance levels and amount of television viewed. A regression analysis was run. Independent T-tests were run for three categories of television viewing (e.g. news, sitcoms, and game shows) as part of a quasi-experiment. Individuals were coded as either high in viewing or low in viewing dependent on shows they listed on survey and pre-made categories they checked off on survey. T-tests were run for categories reported viewed during college only.

Results

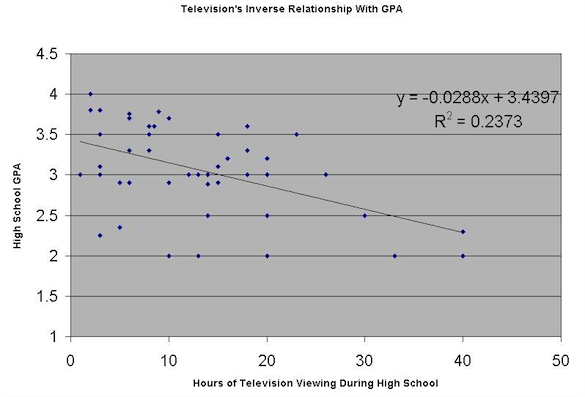

A Pearson r correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationship between amounts of television viewed and GPA levels. This was done for both reported high school and college levels. As predicted, results show that high school GPA was negatively correlated with amounts of television viewed (r(49) = -0.487, p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 1. Also as predicted, there was no significant relationship between college GPA and amounts of television viewed.

A regression analysis was run, which attempted to predict college GPA. High school amounts of television viewed, college amounts of television viewed, and high school GPA were predictors. No significance was found. An independent T-test was run for each of three different categories of television viewing (e.g. news, sitcoms, and game shows) as part of a quasi-experiment. Each category was examined against college GPA. The T-tests were only run for those categories reported viewed at the college level. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences found for any of the three categories.

Table 1: Independant T-Tests for Types of Television Programming

| Variable | Watched Frequently | Did Not Watch Frequently | t |

| News | 3.15 (.427) | 2.91 (.637) n = 26 | 1.55 (n.s.) |

| Sitcoms | 2.96 (.532) n = 35 | 3.19 (.590) n = 15 | 1.39 (n.s.) |

| Game Shows | 3.03 (.717) n = 10 | 3.03 (.517) n = 40 | 0.0(n.s.) |

Note: standard deviations in parentheses.

Figure 1. Inverse relationship between amounts of television viewed during high school and high school GPA.

Discussion

The results support the hypothesis that the more television high school students watch, the lower their GPAs. Since there is a large ongoing debate as to television's effects on school performance levels (Hargborg, 1995; MacBeth, 1996; Childers & Ross, 1973; Williams, Haertel, Haertel, & Walberg, 1982), such findings help to validate the results of past research indicating there is indeed an inverse relationship. One such example was research conducted by Morgan and Gross (1984), who also found larger amounts of television watching associated with lower grades.

This research was also able to include a previously unexamined group. No studies found included college age participants. This has offered new information as to television's effect on school performance levels, particularly at the college level. There was no relationship between college GPA and amounts of television viewing. This may be due to time available for college students to view television. Since many college students work, run households, and/or spend much of their free time studying, it may be that such activities leave less time to spend watching television.

Since amounts of television viewed during high school was correlated with high school GPA, whereas amounts of television viewed during college had no effect on college GPA, there may be the possibility of implicating age as a factor. Television may have less effect on individuals as they get older. It is impossible to know from current research which, if any, of these alternative explanations are the link between television and GPA. This research did not examine any evidence concerning these possibilities due to both time and financial constraints. Further research should be conducted aimed specifically at why there are these differences between the high school and college relationships involving amounts of television viewed and school performance levels.

It may be best to question high school students as to their viewing habits. Following these same students to college to examine individual differences in the amounts of television viewing may be beneficial since the findings of this research were unable to predict college GPA from amounts of television watched during high school or college, or high school GPA. The latter is of some concern. Although, this research was not particularly designed to deal with this issue of using high school GPA as a predictor of college GPA, it is usually one of the most reliable methods available. Due to limitations of this research, GPA's were self-reported by participants. Future research could avoid such error by examining documented records.

The findings of the quasi-experimental research did however indicate, that type of programs watched did not have an effect on overall GPA. Out of three separate categories of television programming, (e.g. news, sitcoms, and game shows) no relationship was found linking high or low levels of watching a particular category to a high or low college GPA. Unfortunately, due to the constraints upon this research these findings were not fully investigated. Other categories were not included and need further investigation. It is the intention of the researcher to expand the current research by adding other such categories previously not considered, and to concentrate solely on any existing relationships between these categories and GPA.

The author would like to thank Dr. Schult for her guidance and assistance during the entire research process, the psychology lab, especially Laura Talcott, for efforts in gathering participants and usage of laboratory materials, and the participants for providing needed data.