During the 1980s, as U.S. workers began to use computing technology, users were thought to need mathematical skills and perceived as a masculine activity (Brosnan 1998). During the 1990s, as computer technology moved from mainframe computing to desktop computing, more workers encountered computers that were user-friendly, with double-click methods, icons, and drag down menus. As computer technology progressed, both older and younger individuals gained experience with computers.

Today, computer technology touches all our lives in many ways, such as on-line banking, ATM's, on-line shopping, automatic bill paying, word processing, and computer games. Organizations today need more and more knowledge workers1, often seeking younger workers to meet this demand. Knowledge workers tend to be viewed as younger, recent college graduates, rather than older individuals who have been in the workforce for 10-20 years. Because schools and colleges are perceived as introducing computer technology (word processing, presentation software, e-mail, etc.) in almost all aspects of education (writing term papers, in-class presentations, etc.), younger individuals are seen as having more experience with computer technology than older workers who completed their education years ago. These perceptions reinforced problematic stereotypes of older workers.

Due to these stereotypes, employers may inadvertently classify older workers as being less healthy, having decreased cognitive abilities, and not as interested or willing to learn new technology (Sharit et al. 1998; Thimm et al. 1998). According to Czaja (1996), cognitive abilities actually decline in most component processes as an individual ages. Panek (1997) stated that the tendency to slow down in performance and behavior with age occurs because older workers prefer accuracy to speed. Unfortunately, these changes contribute to the stereotype that older individuals are not capable of keeping up with the changing workplace. According to Panek (1997), the lack of research directly focused on cognitive aging and issues related to the older worker may also preserve age stereotypes. The assumption that older individuals are disinterested in learning new technologies is another aspect of age stereotyping (Thimm et al. 1998). As computer technology continues to increase, there is reason to believe that stereotypes of older versus younger workers also will continue.

Stereotypes of older versus younger workers compound the challenge for organizations to find more knowledge workers. It is predicted that by 2025 those aged 65 or more will increase three-fold (Czaja 1996). Furthermore, the 25 to 34 age group will have declined as the 45 to 54 age group grows (Valentine et al. 1998). The decline of younger workers, referred to as Generation X, adds to the difficulty in organizations finding knowledge workers.

Although some Baby Boomers attended colleges that used computer technology as an educational tool, many did not have access to computer technology until it was integrated into the work environment. Employers seeking knowledge workers may overlook the hands-on education and/or computer-related classes of older workers. Exposure and experience with computer technology comes not only from educational institutions, but friends, relatives, children, and co-workers. These sources have created a network of sharing knowledge that has enabled the older worker to learn computer technology. In addition, computer technology, from communication with others through e-mail to the assistance in health care, has enabled, and in some respect, forced older individuals to at least learn the basics of computer technology (keyboarding, turn the computer on and off, double clicking, etc.). Also, the easy access to computer technology through libraries, schools and other facilities, the lower costs of computers allowing virtually everyone the possibility of having a computer in their home, to user-friendliness, has created a world in which computer technology is easily accessible. Due to these factors, age should be ignored when seeking knowledge workers, and the focus should be on an applicant's computer experience as judged from the resume and/or interview.

Some past research on experience and anxiety (Czaja 1998; Dyck 1994; Sharit et al. 1998; Marquie 1994) has found differences between older and younger individuals. Findings included older individuals as having higher levels of discomfort, feelings of dehumanization, less control when using computers and lower efficacy (belief that one can perform adequately when using computer technology). It was also found that physical demand and discomfort remained relatively consistent for both older and younger individuals and older individuals experienced less stress than younger individuals when performing information retrieval tasks that were interactive. In addition, it was also found that older individuals have lower levels of computer anxiety even though overall, they had less computer confidence than younger individuals. Despite these differences, a common theme was found in that the level of anxiety was not contingent on age but on experience.

Experience was also related to attitudes toward computers and computer technology in that attitude was not contingent on age, but that experience was also related to positive and negative attitudes. All the studies cited recruited individuals from the community or local universities to participate in the research. This study differs in that the participants were employed and based their responses on current day-to-day work situations, making anxiety based solely on the present work situation(s) and limiting anxiety effects when leaving one environment and entering into the research environment where individuals are taken out of their work environment and placed into a laboratory where they perform simulated tasks. Another strength of this study is its recency: the increase in additional technology, such as ATM's, electronic banking, health care delivery, education, and personal communication, has given individuals of all ages experience with technology. These advances have aided in "leveling the playing field" for workers, so that older and younger individuals in this study may have similar levels of computer experience.

The primary objective of the present study was to determine whether age or experience better predicts anxiety toward computers and computer technology. Based on previous research and the rapid increase and changes in computer technology, it was hypothesized that experience, not age, predicts computer anxiety.

METHOD

A total of 288 questionnaire packets (consisting of a cover letter, instruction sheet, two consent forms, questionnaire, two ticket stubs with identical numbers, debriefing statement, and a return-stamped envelope) were given to two temporary agencies for distribution in one of two ways: 1) direct mailing to all employees of the agency or 2) inserted with paychecks that were picked up or mailed. Both methods of distribution ensured the confidentiality and anonymity of participants.

Employees who chose to participate returned the questionnaire, one signed or initialed consent form, and one ticket stub. Upon receipt, questionnaires and consent forms were placed in two separate boxes so that all responses would remain anonymous. Tickets were removed and entered into a drawing to win $50.00. The winning ticket number was given to both temporary agencies and all employees were notified by either placing an announcement with all paychecks or in a company newsletter. The participant winning the drawing provided the matching ticket, as required, to claim the $50.00.

A total of 57 questionnaires were returned (one of these was eliminated due to missing data). The sample was comprised of 17.9% males and 82.1% females from two local temporary employment agencies in the South Bend-Mishawaka Community. Temporary employment agencies were used in this study because they place individuals in a wide variety of occupations. Participation was on a voluntary basis. The ages of participants ranged from 19 to 67 with a mean age of 35. Forty-six percent of the participants were age 30 or younger, and fifty-four percent were over the age of 30. All participants were employed (8.8% accounting/finance; 50.9% clerical/office support; 5.3% factory; 5.3% information technology; 1.8% laborer; 3.5% manufacturing; 1.8% PC & networking support; 1.8% supervisor; 1.8% warehouse; and 19.3% other).

The questionnaire included a 16-item performance measure designed to assess frequency of use of hardware and software (Harrison et al. 1997). This measure was used to obtain employees' computer experience. Participants were asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert scale (a rating scale that presents the examinee with five responses ordered on a continuum) from 1 (Never) to 5 (Daily). Hardware sources included the workstation, microcomputer, mainframe, and minicomputer. Software activities were word processing, spreadsheets, database, communications, graphics, desktop publishing, project management, integrated packages, and statistics. An example item on the frequency of use is "How often do you use a personal or desktop computer?" An additional measure of computer experience consisted of a single, global item based on information from Czaja and Sharit (1998). The item asked participants to rate their level of computer experience as having no experience, very little experience (infrequent use and very little knowledge), or moderate experience (knowledge of a few applications and occasional use).

Another component of the questionnaire was the 20-item Computer Anxiety Scale (CAS) of Marcoulides (1989), that measures the perception held by an individual of their anxiety in different situations related to computers. Subjects used a five-point Likert format to reflect anxiety ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). The CAS has two factors: general computer anxiety (anxiety from direct experiences using a computer; the role of computers in society, and the impact of computers on workers in the work environment) and equipment anxiety (actual use of equipment). Higher scores indicate more self-reported anxiety. An example item is "I feel anxious when using new software packages." The questionnaire also contained 6 demographic questions: year of birth, gender, number of years of formal education, race, occupation, and marital status. Age was date of birth.

RESULTS

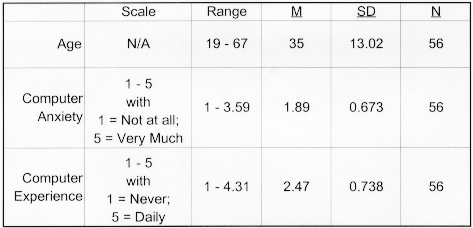

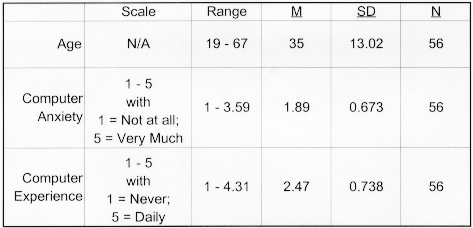

The primary hypothesis states that experience is a better predictor than age of anxiety toward computers and computer technology. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for age, anxiety, and experience. Pearson correlations (a statistic used to measure the strength of linear association between two variables) were calculated among age, computer experience and computer anxiety. There was a significant (negative) relationship between computer experience and computer anxiety (r = -0.400, p<0.01), indicating individuals with more computer experience have less computer anxiety. There was no significant relationship between age and computer anxiety (r = 0.17, ns), indicating that age is not a predictor of computer anxiety. Moreover, there was no significant relationship between computer experience and age (r = -0.11, ns). Thus, age does not predict computer experience.

A multiple regression (combined relationship between two or more predictors and the criterion) was used to predict computer anxiety as a function of experience and age. Experience alone predicted computer anxiety (R2= 0.16, p < 0.01). The combination of age and experience also predicted computer anxiety (R2= 0.18, p < 0.01), but the regression coefficient of the age variable was not significant (t = 1.00, ns). These results confirm the hypothesis that experience is a better predictor than age of computer anxiety.

Descriptive statistics for age, computer anxiety

and computer experience

Table 1. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; N = number of respondents.

DISCUSSION

This research demonstrates that computer experience, not age, predicts computer anxiety. Results of the present study, taken together with the earlier findings of Czaja & Sharit (1998) and Marquie & Baracat (1994), discredit the stereotype of older persons as too anxious about computers to serve as knowledge workers. The relative increase of older workers (Baby Boomers) compared to younger workers (Generation X) should seem less dire if employers recognize computer experience, and not age, as the critical issue. Moreover, results of this study are consistent with the scenario that, as technology increases, so do the skills and experience of workers of all ages.

Employers should no longer "judge a book by its cover." They should focus on an employee's computer experience and ignore age. As experience increases, computer anxiety decreases in older and younger workers. This is demonstrated in the sample of workers recruited from temporary agencies who frequently have to adapt to technological changes as they work in various environments. Although these findings supported some previous studies, the present study was conducted in the work environment, as opposed to a research setting (an environment outside of their daily work or home where they are typically placed into a laboratory to perform simulated tasks). It also took into account the rapid changes in computer technology that workers face on a daily basis when they are sent to different work environments. Lastly, this sample included a wide range of ages and occupations (i.e., clerical/office support, accounting/finance, manufacturing, networking support, warehouse workers, etc.).

This study does have several characteristics that may limit the ability to generalize the results. First, these results, based on workers from temporary employment agencies, may not represent permanent workers, as temporary workers receive more training on current computer technology than permanent workers. Second, there could be a lack of representativeness due to the large percentage of female participants (82.1%) and of clerical/office employees (50.9%). Thirdly, the sample size was unfortunately small, and the response rate was not as high as expected, despite several follow-up letters and notification in agency newsletters.

Due to these limitations, future studies in this line of research should include larger representative samples of permanent workers. Future research will investigate whether age is related to attitudes of computer technology or self-efficacy (belief that one can perform adequately in using computer technology). Additional research will compare a worker's attitude, computer anxiety, and self-efficacy under "normal" working conditions versus when a computer is "down," to see if age and/or experience are predictive factors.

1Knowledge worker(s) is a term used to describe potential employees who have immediate utility; an individual with the skills, knowledge and ability to meet requirements; oftern used when referring to technology workers or those with computer technology experience with software and/or hardware. (Yeatts et al. 1999; Harison et al. 1995)